I generally don’t think it’s terribly interesting to point out someone else’s hypocrisy. Judging from the internet, mine is not a popular view. You’ll find all kinds of this style of argument, if you dare to look:

“How can you support X when you didn’t support Y?”

“How can you complain about A when B didn’t bother you?”

X, Y, A, and B can be anything you like, really. Claims of corruption in your party vs. comparable claims of comparable corruption in the other party. Trust in one scientific consensus and distrust in another one. Tolerating speeding but not jaywalking, I don’t know.

Too often, this is a bad move, as it exposes both parties’ hypocrisy (after all, if I support Y but not X, it doesn’t really put me in a good light to complain about someone else supporting X but not Y. If my claim is that X and Y are equivalent, then we’re both hypocrites.) Plus, I find it a bit dull. And worst of all, it doesn’t ever seem to move people, so it’s just fighting for fighting’s sake, which is basically my least favorite thing.

But!

Isn’t it interesting that…

I just find it funny how…

A lot of folks were complaining about government overreach recently, protesting in vivid libertarian terms about their rights not to comply with public-health orders.

And then—

(Here comes my least favorite style of argument, out of my own lips/fingers)—

The! same! folks!

Are now complaining about other people’s unwillingness to comply with curfews and every other trapping of what we might call “public order” orders.

To the extent that the argument is simply “you must do what the government says,” then all of us should be on the same side of both of these fights.

Obviously, it’s more complicated than that.

But I’m interested right now in that complication. Why are the cases different? Not morally (because the moral case is, I think, obvious, and has been stated by many people a lot more articulately than I could state it). But psychologically: how do we arrive at these different takes on what looks like a similar issue? And how do we justify it?

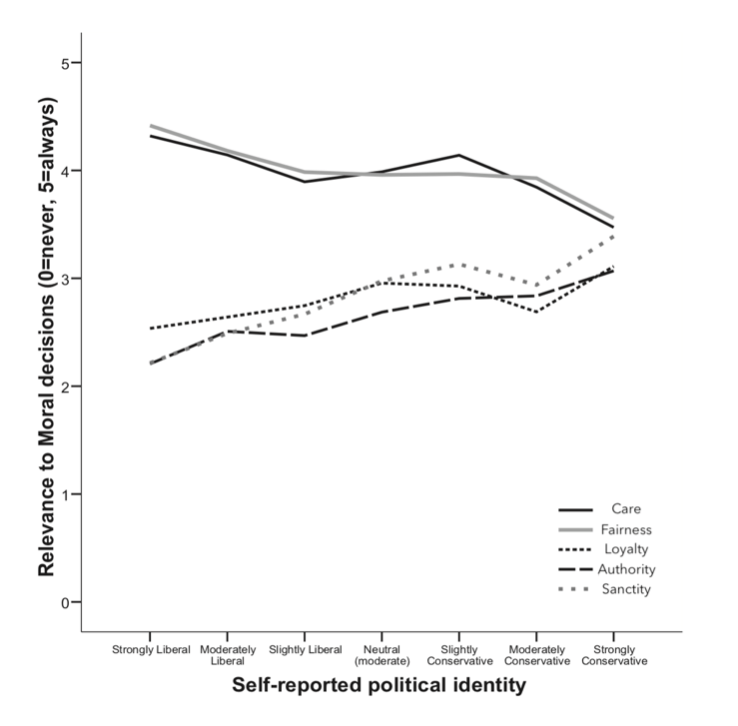

I’ve written before here about the moral tastebuds, which I think are a helpful tool. (Remember: all models are wrong, but some are useful.) When applied to politics, researchers have found that American liberals tend to emphasize the tastebuds of “caring for others” and “fairness” much more highly than the other tastebuds. By contrast, American conservatives’ tastebuds are all over the map—they are motivated by authority, sanctity, liberty, loyalty, fairness, and yes, care. In other words, the more conservative someone is, the more they’re motivated by all the tastebuds more or less equally.

(Note that “liberty” is a tastebud the researchers added to the system later, so it doesn’t appear on the chart).

I’ve always thought it was interesting that we all, to varying degrees, have to balance two tastebuds that are contradictory to each other: liberty and authority. How do we do it? And how, particularly, do the most strongly conservative people balance these tastebuds, as they care about them the most?

Well, here’s a bit of an answer, looking at the last few weeks of conservatives decrying any amount of disorder and opposition to the government, forgetting all about their Gadsden flags and cries for liberty.

The answer is racism, friends.

Disorder, rebellion, and resistance are all well and good when we are doing them; when it’s our interests at stake. But when they are making me uncomfortable, causing a ruckus? Shut it down.

Because, the psychology goes, they need to make me comfortable above all. My comfort requires their silence and compliance. My comfort is more important than their rights and even their lives.

Comfort, then—and the racism it perpetuates among white people—is the silent tastebud that tells us when to care and when not to. When to fight for liberty and when to demand submission. When we must fight for fairness and when we can accept injustice.

We have to let it go.

Anyway, here’s a cool frog I saw last weekend.